China's Innovation Comeback Rooted in Tradition

At a recent roundtable on Tiangong Kaiwu, a 17th-century Chinese encyclopedia of crafts, Li Bo, a renowned cultural scholar and professor at Nanjing Normal University, dubbed the book "a DeepSeek of 400 years ago." That comparison — linking an early repository of practical knowledge to a modern open-source AI model — reveals a deeper truth: China's contemporary surge in innovation is less of a sudden rise and more of a revival rooted in a long civilizational habit of problem-solving and practical inquiry.

For a long time, popular narratives of Western media doubled down on the idea that modern China was somehow alien to innovation. They often portrayed Chinese innovation as a "follower" or "challenger," habitually framing it in zero-sum terms like a "race."

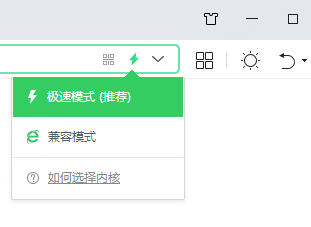

DeepSeek's open-source practice, however, tells a different story: China's innovation is not about building technological walls but about constructing bridges for cooperation; not about hoarding results but about promoting shared benefits.

This open and inclusive spirit is continuous with the historical role of Tiangong Kaiwu after its transmission to Europe, which helped spur technological exchange. Just as technologies recorded in the book — such as patterned looms and steel-casting methods — once benefited the world, today's Chinese digital innovations also aim to become global digital public goods.

From a broader perspective, DeepSeek is not an isolated case. Practices like opening China's FAST to global observations, providing the BeiDou satellite navigation system to the world, and carrying international payloads on the Chang'e-6 lunar missions, help outline a new paradigm of Chinese innovation: rooted in the cultural tenet of "If you want to make a stand, help other make a stand, and if you want to reach your goal, help other reach their goal," replacing technological closure with open cooperation and zero-sum competition with inclusive sharing.

This paradigm not only counters the framing of Chinese technological rise as an isolated, competitive threat but also repositions it as a public tool to address humanity's common challenges.

As the Chinese civilization has long emphasized "applying knowledge to practical affairs" and the integration of technology with people's livelihoods, this pragmatic and open tradition of innovation is the cultural foundation that enables modern Chinese science and technology to be rapidly translated into applications that serve society.

China's juncao (fungus grass) technology has been promoted to more than a hundred countries, effectively helping Pacific Island nations reduce poverty; its hybrid rice has been planted in Southeast Asian and African countries, supporting local people to solve the food shortage; and its new energy vehicles drive around the globe, beneficial to a cleaner, greener world.

To see China's sci-tech developments through a civilizational lens, you can understand that its innovation can contribute to a broader, shared renaissance of science and technology — one that serves not just national ambitions but global needs.